Diátaxis is a way of thinking about and doing documentation.

It prescribes approaches to content, architecture and form that emerge from a systematic approach to understanding the needs of documentation users.

Diátaxis, from the Ancient Greek δῐᾰ́τᾰξῐς: dia (“across”) and taxis (“arrangement”).

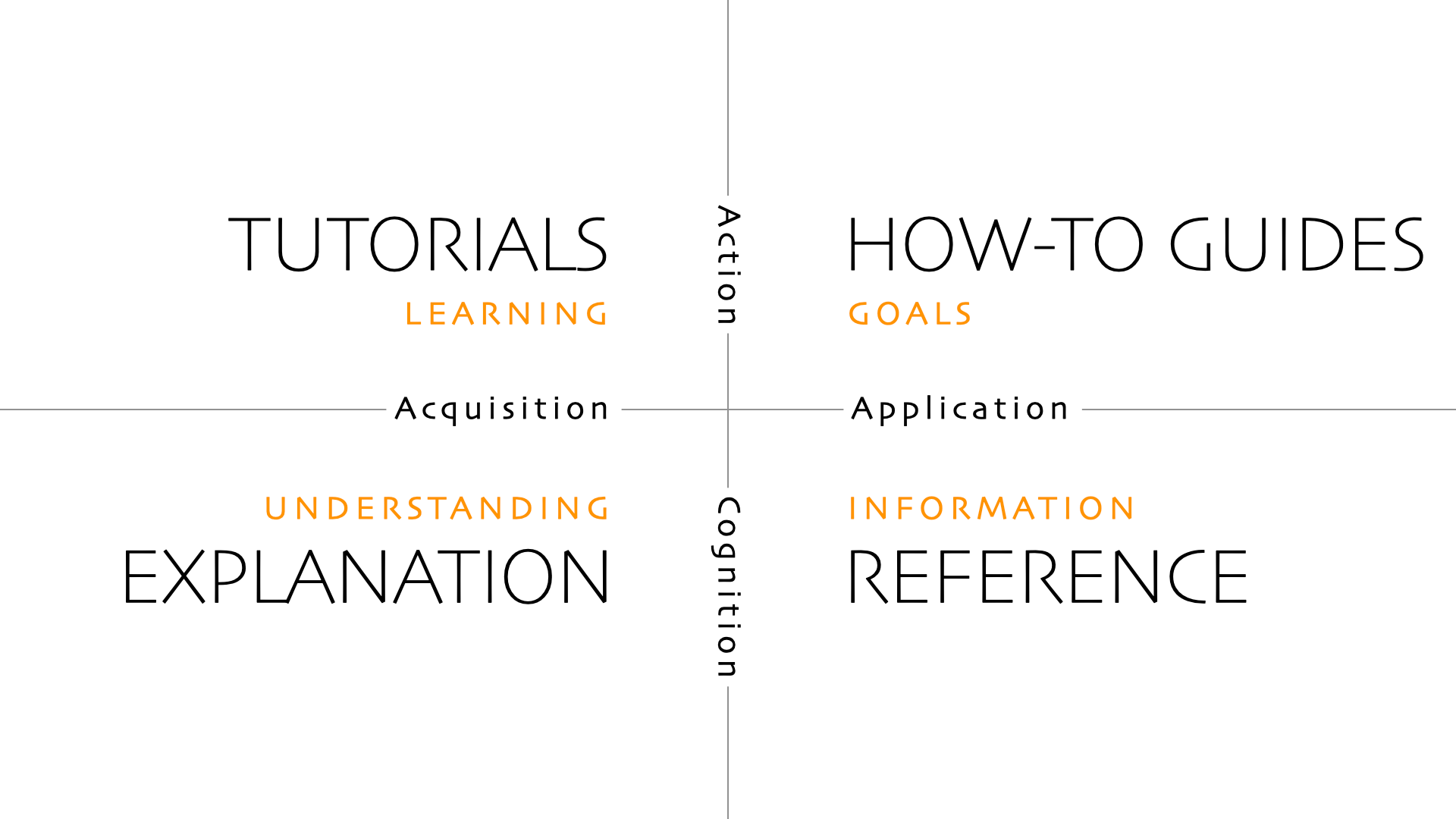

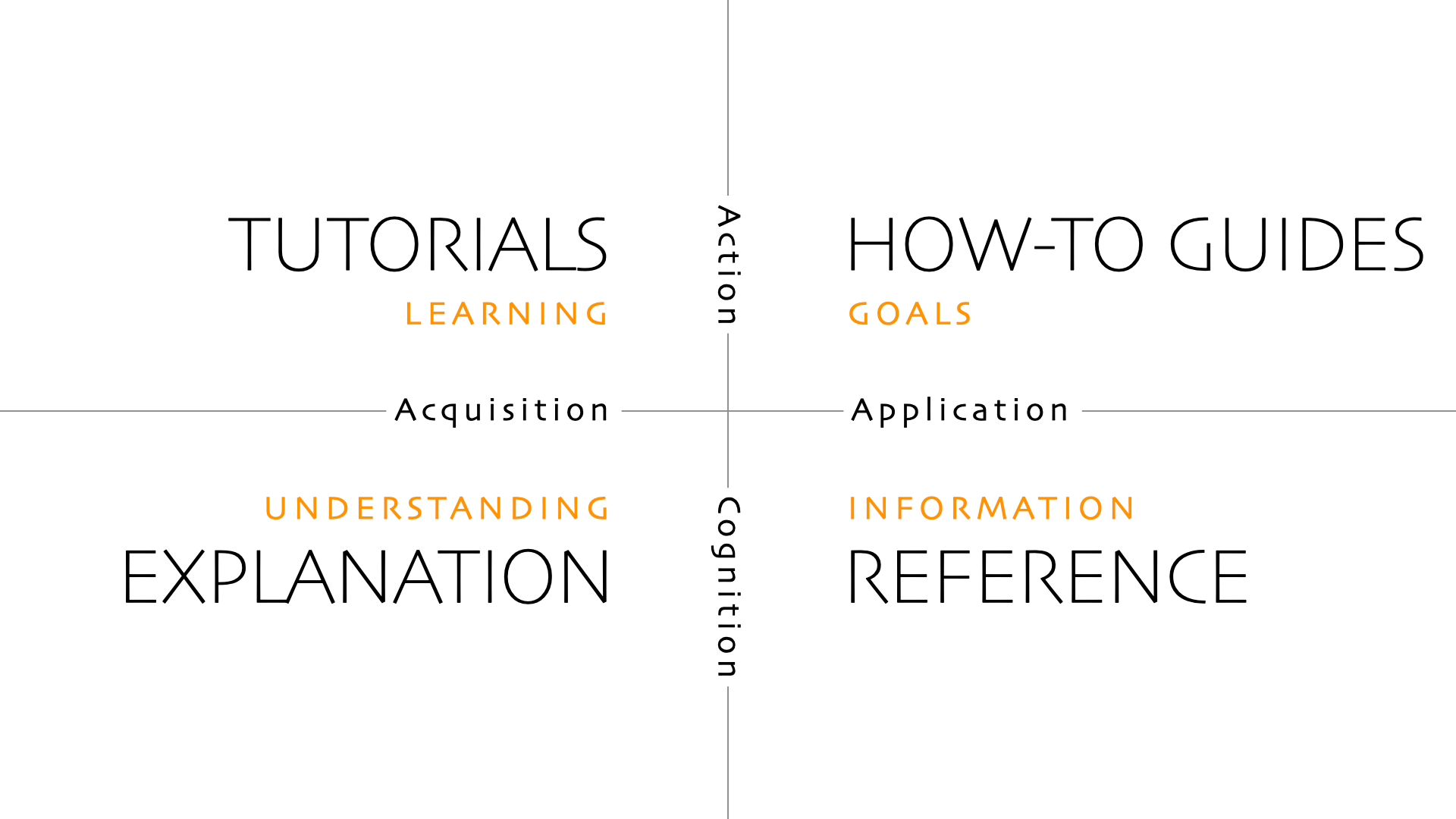

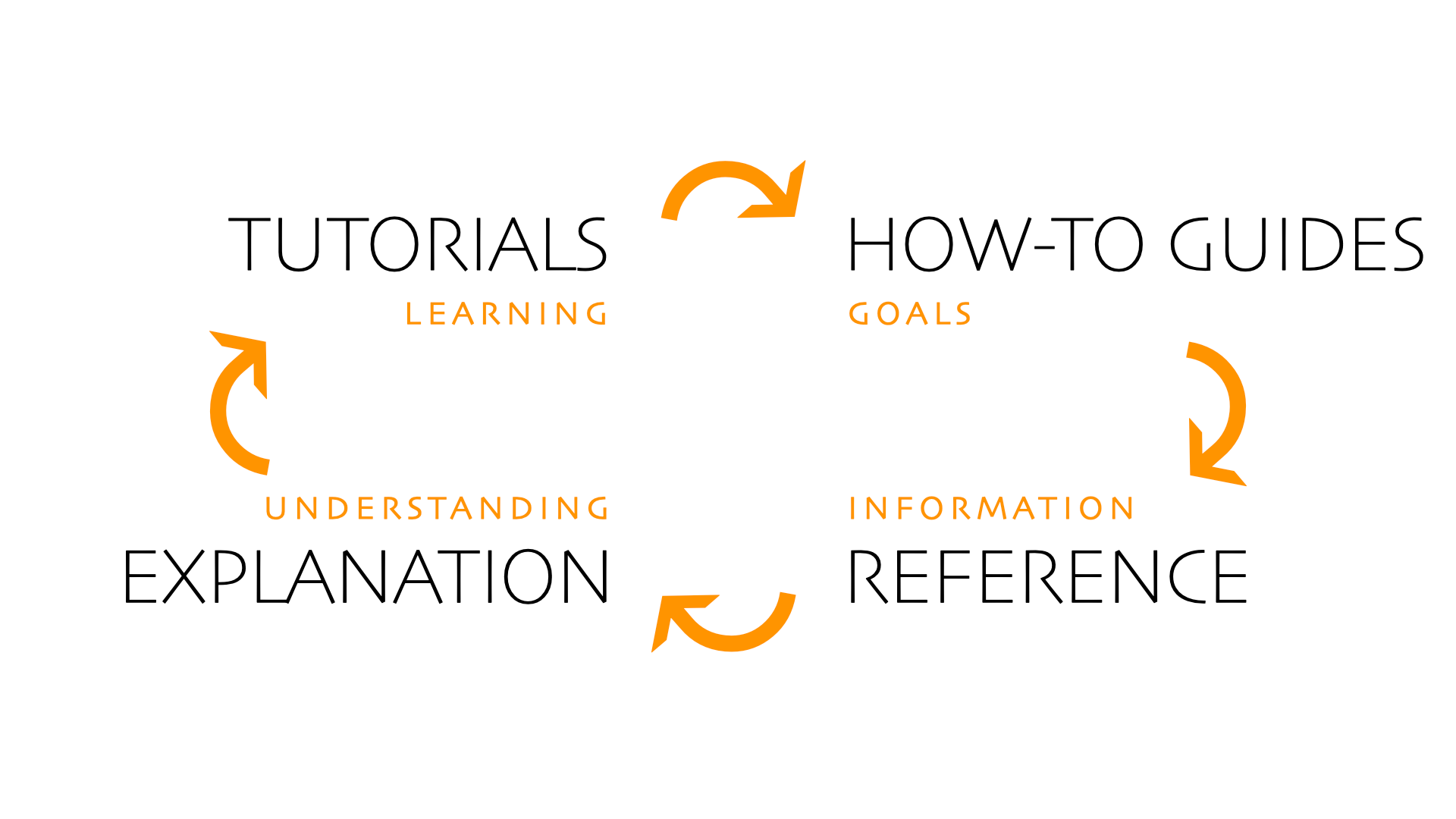

Diátaxis identifies four distinct needs, and four corresponding forms of documentation - tutorials, how-to guides, technical reference and explanation. It places them in a systematic relationship, and proposes that documentation should itself be organised around the structures of those needs.

Diátaxis solves problems related to documentation content (what to write), style (how to write it) and architecture (how to organise it).

As well as serving the users of documentation, Diátaxis has value for documentation creators and maintainers. It is light-weight, easy to grasp and straightforward to apply. It doesn’t impose implementation constraints. It brings an active principle of quality to documentation that helps maintainers think effectively about their own work.

Contents

This website is divided into two main sections, to help apply and understand Diátaxis.

Start here. These pages will help make immediate, concrete sense of the approach.

This section explores the theory and principles of Diátaxis more deeply, and sets forth the understanding of needs that underpin it.

- Understanding Diátaxis

- Foundations

- The map

- Quality

- Tutorials and how-to guides

- Reference and explanation

- Complex hierarchies

Diátaxis is proven in practice. Its principles have been adopted successfully in hundreds of documentation projects.

At Gatsby we recently reorganized our open-source documentation, and the Diátaxis framework was our go-to resource throughout the project. The four quadrants helped us prioritize the user’s goal for each type of documentation. By restructuring our documentation around the Diátaxis framework, we made it easier for users to discover the resources that they need when they need them.

While redesigning the Cloudflare developer docs, Diátaxis became our north star for information architecture. When we weren’t sure where a new piece of content should fit in, we’d consult the framework. Our documentation is now clearer than it’s ever been, both for readers and contributors.

The pages in this section are concerned with putting Diátaxis into practice.

Diátaxis is underpinned by systematic theoretical principles, but understanding them is not necessary to make effective use of the system.

Diátaxis is primarily intended as a pragmatic approach for people working on documentation. Most of the key principles required to put it into practice successfully can be grasped intuitively.

Don’t wait to understand Diátaxis before you start trying to put it into practice. Not only do you not need to understand it all to make use of it, you will not understand it until you have started using it (this itself is a Diátaxis principle).

As soon as you feel you have picked up an idea that seems worth applying to your work, try applying it. Come back here when you need more clarity or reassurance. Iterate between your work and reflecting on your work.

In this section

At the core of Diátaxis are the four different kinds of documentation it identifies. If you’re encountering Diátaxis for the first time, start with these pages.

- Tutorials - learning-oriented experiences

- How-to guides - goal-oriented directions

- Reference - information-oriented technical description

- Explanation - understanding-oriented discussion

Diátaxis prescribes principles that guide action. These translate into particular ways of working, with implications for documentation process and execution. Once you’ve made your first start, the tools and methods outlined here will help smooth your way.

- The compass - a simple tool for direction-finding

- Workflow in Diátaxis

A tutorial is an experience that takes place under the guidance of a tutor. A tutorial is always learning-oriented.

A tutorial is a practical activity, in which the student learns by doing something meaningful, towards some achievable goal.

A tutorial serves the user’s acquisition of skills and knowledge - their study. Its purpose is not to help the user get something done, but to help them learn.

A tutorial in other words is a lesson.

It’s important to understand that while a student will learn by doing, what the student does is not necessarily what they learn. Through doing, they will acquire theoretical knowledge (i.e. facts), understanding, familiarity. They will learn how things relate to each other and interact, and how to interact with them. They will learn the names of things, the use of tools, workflows, concepts, commands. And so on.

A lesson entails a relationship between a teacher and a pupil. In all learning of this kind, learning takes place as the pupil applies themself to tasks under the instructor’s guidance.

A lesson is a learning experience. In a learning experience, what matters is what the learner does and what happens. By contrast, the teacher’s explanations and recitations of fact are far less important.

A good lesson gives the learner confidence, by showing them that they can be successful in a certain skill or with a certain product.

It’s not easy being a teacher.

A lesson is a kind of contract between teacher and student, in which nearly all the responsibility falls upon the teacher. The teacher has responsibility for what the pupil is to learn, what the pupil will do in order to learn it, and for the pupil’s success. Meanwhile, the only responsibility of the pupil in this contract is to be attentive and to follow the teacher’s directions as closely as they can. There is no responsibility on the pupil to learn, understand or remember.

At the same time, the exercise you put your pupils through must be:

- meaningful - the pupil needs to have a sense of achievement

- successful - the pupil needs to be able to complete it

- logical - the path that the pupil takes through it needs to make sense

- usefully complete - the pupil must have an encounter with all of the actions, concepts and tools they need to become familiar with

In general, tutorials are rarely done well, partly because they are genuinely difficult to do well, and partly because they are not well understood. In software, many products lack good tutorials, or lack tutorials completely; tutorials are often conflated with how-to guides.

In an ideal lesson, the teacher is present and interacts with and responds to the student, correcting their mistakes and checking their learning. In documentation, none of this is possible.

Writing and maintaining tutorials can consume a remarkable amount of effort and time.

It’s hard enough to put together a learning experience that meets all the standards described above; in many contexts the product itself evolves rapidly, meaning that all that work needs to be done again to ensure that the tutorial still performs its required functions.

You will also often find that no other part of your documentation is subject to revisions the way your tutorials are. Elsewhere in documentation, changes and improvements can generally be made discretely; in tutorials, where the end-to-end learning journey must make sense, they often cascade through the entire story.

Finally, tutorials contain the additional complication of the distinction between what is to be learned and what is to be done. Not only must the creator of a tutorial have a good sense of what the user must learn, and when, they must also devise a meaningful learning journey that somehow delivers all that.

A tutorial is a pedagogical problem.

It’s not an easy problem, but neither is it a mystery. The principles outlined below - repetition, action, small steps, results early and often, concreteness and so on - are not secrets, but they are not always well understood.

Still, there are straightforward, effective ways to address the problems of pedagogy in practice.

Anti-pedagogical temptations

- abstraction, generalisation

- explanation

- choices

- information

The first rule of teaching is simply: don’t try to teach. Your job, as a teacher, is to provide the learner with an experience that will allow them to learn. A teacher inevitably feels a kind of anxiety to impart knowledge and understanding, but if you give into it and try to teach by telling and explaining, you will jeopardise the learning experience.

Instead, allow learning to take place, and trust that it will. Give your learner things to do, through which they can learn. Only your pupil can learn. Sadly, however much you desire it, you will not be able to learn for your pupil. You cannot make them learn. All you can do is make it so they can learn.

It’s important to allow the learner to form an idea of what they will achieve right from the start. As well as helping to set expectations, it allows them to see themselves building towards the completed goal as they work.

Providing the picture the learner needs in a tutorial can be as simple as informing them at the outset: In this tutorial we will create and deploy a scalable web application. Along the way we will encounter containerisation tools and services.

This is not the same as saying: In this tutorial you will learn… - which is presumptuous and a very poor pattern.

Your learner is probably doing new and strange things that they don’t fully understand. Understanding comes from being able to make connections between causes and effects, so let them see the results and make the connections rapidly and repeatedly. Each one of those results should be something that the user can see as meaningful.

Every step the learner follows should produce a comprehensible result, however small.

At every step of a tutorial, the user experiences a moment of anxiety: will this action produce the correct result? Part of the work of a successful tutorial is to keep providing feedback to the learner that they are indeed on the right path.

Keep up a narrative of expectations: “You will notice that …”; “After a few moments, the server responds with …”. Show the user actual example output, or even the exact expected output.

If you know know in advance what the likely signs of going wrong are, consider flagging them: “If the output doesn’t show …, you have probably forgotten to …”.

It’s helpful to prepare the user for possibly surprising actions: “The command will probably return several hundred lines of logs in your terminal.”

Learning requires reflection. This happens at multiple levels and depths, but one of the first is when the learner observes the signs in their environment. In a lesson, a learner is typically too focused on what they are doing to notice them, unless they are prompted by the teacher.

Your job as teacher is to close the loops of learning by pointing things out, in passing, as the lesson moves along. This can be as simple as pointing out how a command line prompt changes, for example.

Observing is an active part of a craft, not a merely passive one. It means paying attention to the environment, a skill in itself. It’s often neglected.

In all skill or craft, the accomplished practitioner experiences a feeling of doing, a joined-up purpose, action, thinking and result.

As skill develops, it flows in a confident rhythm and becomes a kind of pleasure. It’s the pleasure of walking, for example.

Pay attention to your own feeling of doing in your work. What is it like to perform a particular operation?

Your learner’s skill depends upon their discovering this feeling, and its becoming a pleasure.

Your challenge as the creator of a tutorial is to ensure that its tasks tie together purpose and action so they become a cradle for this feeling.

Learners will return to and repeat an exercise that gives them success, for the pleasure they find in getting the expected result. Doing so reaffirms to them that they can do it, and that it works.

Repetition is a key to establishing the feeling to doing; being at home with that feeling is a foundational layer of learning.

Repetition is not the best teacher - sometimes it’s the only teacher.

In your tutorial, try to make it possible for a particular step and result to be repeated. This can be difficult, for example in operations that are not reversible (making it hard to go back to a previous step) - but seek it wherever you can. Watching a user follow a tutorial, you may often be amazed to see how often they choose to repeat a step. They are doing it just to see that the same thing really does happen again.

A tutorial is not the place for explanation. In a tutorial, the user is focused on correctly following your directions and getting the expected results. Later, when they are ready, they will seek explanation, but right now they are concerned with doing. Explanation distracts their attention from that, and blocks their learning.

For example, it’s quite enough to say something like: We’re using HTTPS because it’s more secure. There is a place for extended discussion and explanation of HTTPS, but not now. Instead, provide a link or reference to that explanation, so that it’s available, but doesn’t get in the way.

Explanation is only pertinent at the moment the user wants it. It is not for the documentation author to decide.

Explanation is one of the hardest temptations for a teacher to resist; even experienced teachers find it difficult to accept that their students’ learning does not depend on explanation. This is perfectly natural. Once we have grasped something, we rely on the power of abstraction to frame it to ourselves - and that’s how we want to frame it to others. Understanding means grasping general ideas, and abstraction is the logical form of understanding - but these are not what we need in a tutorial, and it’s not how successful learning or teaching works.

One must see it for oneself, to see the focused attention of a student dissolve into air, when a teacher’s well-intentioned explanation breaks the magic spell of learning.

In a learning situation, your student is in the moment, a moment composed of concrete things. You are responsible for setting up and maintaining the student’s flow, from one concrete action and result to another.

Focus on this problem, this action, this result, in such a way that you lead the learner from step to concrete step.

It might seem that by maintaining focus on the concrete and particular that you deny the student the opportunity to see or grasp the larger general patterns, but the contrary is true. The one thing our minds do spectacularly well is to perceive general patterns from concrete examples. All learning moves in one direction: from the concrete and particular, towards the general and abstract. The latter will emerge from the former.

Your job is to guide the learner to a successful conclusion. There may be many interesting diversions along the way (different options for the command you’re using, different ways to use the API, different approaches to the task you’re describing) - ignore them. Your guidance needs to remain focused on what’s required to reach the conclusion, and everything else can be left for another time.

Doing this helps keep your tutorial shorter and crisper, and saves both you and the reader from having to do extra cognitive work.

All of the above are general principles of pedagogy, but there is a special burden on the creator of a tutorial.

A tutorial must inspire confidence. Confidence can only be built up layer by layer, and is easily shaken. At every stage, when you ask your student to do something, they must see the result you promise. A learner who follows your directions and doesn’t get the expected results will quickly lose confidence, in the tutorial, the tutor and themselves.

You are required to be present, but condemned to be absent.

A teacher who’s there with the learner can rescue them when things go wrong. In a tutorial, you can’t do that. Your tutorial ought to be so well constructed that things can’t go wrong, that your tutorial works every user, every time.

It’s hard work to create a reliable experience, but that is what you must aspire to in creating a tutorial.

Your tutorial will have flaws and gaps, however carefully it is written. You won’t discover them all by yourself, you will have to rely on users to discover them for you. The only way to learn what they are is by finding out what actually happens when users do the tutorial, through extensive testing and observation.

- We …

- The first-person plural affirms the relationship between tutor and learner: you are not alone; we are in this together.

- In this tutorial, we will …

- Describe what the learner will accomplish.

- First, do x. Now, do y. Now that you have done y, do z.

- No room for ambiguity or doubt.

- We must always do x before we do y because… (see Explanation for more details).

- Provide minimal explanation of actions in the most basic language possible. Link to more detailed explanation.

- The output should look something like …

- Give your learner clear expectations.

- Notice that … Remember that … Let’s check …

- Give your learner plenty of clues to help confirm they are on the right track and orient themselves.

- You have built a secure, three-layer hylomorphic stasis engine…

- Describe (and admire, in a mild way) what your learner has accomplished.

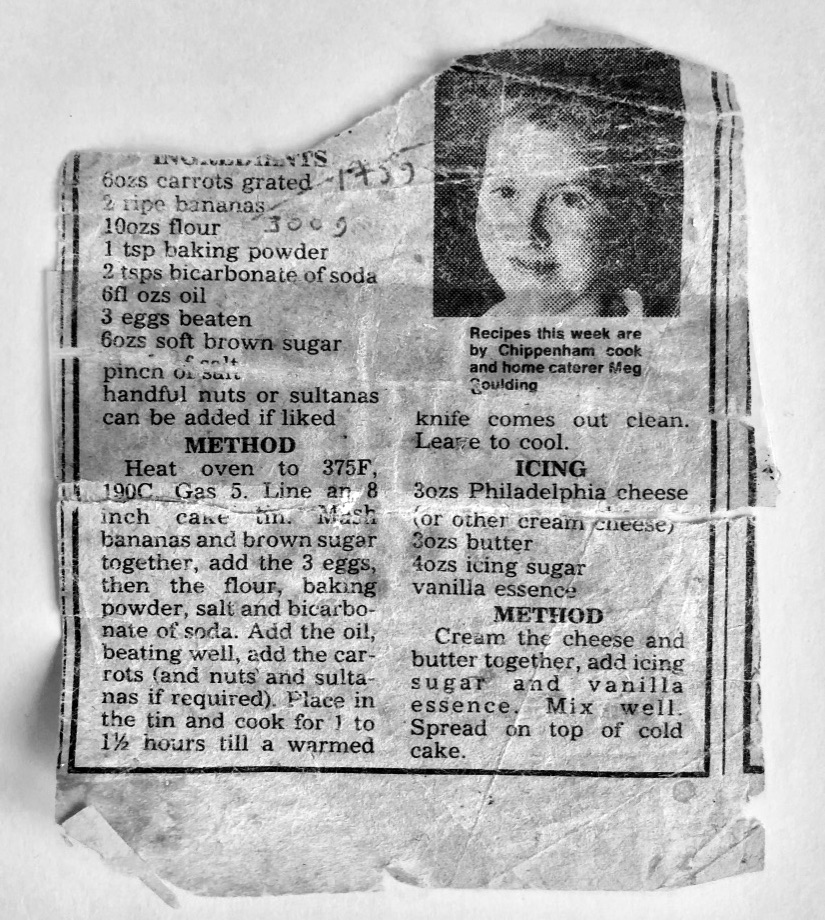

Someone who has had the experience of teaching a child to cook will understand what matters in a tutorial, and just as importantly, the things that don’t matter at all.

It really doesn’t matter what the child makes, or how correctly they do it. The value of a lesson lies in what the child gains, not what they produce.

Success in a cooking lesson with a child is not the culinary outcome, or whether the child can now repeat the processes on their own. Success is when the child acquires the knowledge and skills you were hoping to impart.

It’s a crucial condition of this that the child discovers pleasure in the experience of being in the kitchen with you, and wants to return to it. Learning a skill is never a once and for all matter. Repetition is always required.

Meanwhile, the cooking lesson might be framed around the idea of learning how to prepare a particular dish, but what we actually need the child to learn might be things like: that we wash our hands before handling food; how to hold a knife; why the oil must be hot; what this utensil is called, how to time and measure things.

The child learns all this by working alongside you in the kitchen; in its own time, at its own pace, through the activities you do together, and not from the things you say or show.

With a young child, you will often find that the lesson suddenly has to end before you’d completed what you set out to do. This is normal and expected; children have short attention spans. But as long as the child managed to achieve something - however small - and enjoyed doing it, it will have laid down something in the construction of its technical expertise, that can be returned to and built upon next time.

How-to guides are directions that guide the reader through a problem or towards a result. How-to guides are goal-oriented.

A how-to guide helps the user get something done, correctly and safely; it guides the user’s action.

It’s concerned with work - navigating from one side to the other of a real-world problem-field.

Examples could be: how to calibrate the radar array; how to use fixtures in pytest; how to configure reconnection back-off policies. On the other hand, how to build a web application is not - that’s not addressing a specific goal or problem, it’s a vastly open-ended sphere of skill.

How-to guides matter not just because users need to be able to accomplish things: the list of how-to guides in your documentation helps frame the picture of what your product can actually do. A rich list of how-to guides is an encouraging suggestion of a product’s capabilities.

Well-written how-to guides that address the right questions are likely to be the most-read sections of your documentation.

How-to guides must be written from the perspective of the user, not of the machinery. A how-to guide represents something that someone needs to get done. It’s defined in other words by the needs of a user. Every how-to guide should answer to a human project, in other words. It should show what the human needs to do, with the tools at hand, to obtain the result they need.

This is in strong contrast to common pattern for how-to guides that often prevails, in which how-to guides are defined by operations that can be performed with a tool or system. The problem with this latter pattern is that it offers little value to the user; it is not addressed to any need the user has. Instead, it’s focused on the tool, on taking the machinery through its motions.

This is fundamentally a distinction of meaningfulness. Meaning is given by purpose and need. There is no purpose or need in the functionality of a machine. It is merely a series of causes and effects, inputs and outputs.

Consider:

- “To shut off the flow of water, turn the tap clockwise.”

- “To deploy the desired database configuration, select the appropriate options and press Deploy.”

We really do not need to be informed that we turn on a device using the power switch, but it is shocking how often how-to guides in software documentation are written at this level.

The examples above look like examples of guidance, but they are not.

They represent mostly useless information that anyone with basic competence - anyone who is working in this domain - should be expected to know. Between them, standardised interfaces and generally-expected knowledge should make it quite clear what effect most actions will have.

Secondly, they are disconnected from purpose. What the user needs to know might be things like:

- how much water to run, and how vigorously to run it, for a certain purpose

- what database configuration options align with particular real-world needs

How-to guides are about goals, projects and problems, not about tools.

Tools appear in how-to guides as incidental bit-players, the means to the user’s end. Sometimes of course, a particular end is closely aligned with a particular tool or part of the system, and then you will find that a how-to guide indeed concentrates on that. Just as often, a how-to guide will cut across different tools or parts of a system, joining them up together in a series of activities defined by something a human being needs to get done. In either case, it is that project that defines what a how-to guide must cover.

How-to guides are wholly distinct from tutorials. They are often confused, but the user needs that they serve are quite different. Conflating them is at the root of many difficulties that afflict documentation. See The difference between a tutorial and how-to guide for a discussion of this distinction.

In another confusion, how-to guides are often construed merely as procedural guides. But solving a problem or accomplishing a task cannot always be reduced to a procedure. Real-world problems do not always offer themselves up to linear solutions. The sequences of action in a how-to guide sometimes need to fork and overlap, and they have multiple entry and exit-points. Often, a how-to guide will need the user to rely on their judgement in applying the guidance it can provide.

A how to-guide is concerned with work - a task or problem, with a practical goal. Maintain focus on that goal.

How-to characteristics

- focused on tasks or problems

- assume the user knows what they want to achieve

- action and only action

- no digression, explanation, teaching

Anything else that’s added distracts both you and the user and dilutes the useful power of the guide. Typically, the temptations are to explain or to provide reference for completeness. Neither of these are part of guiding the user in their work. They get in the way of the action; if they’re important, link to them.

A how-to guide serves the work of the already-competent user, whom you can assume to know what they want to do, and to be able to follow your instructions correctly.

A how-to guide needs to be adaptable to real-world use-cases. One that is useless for any purpose except exactly the narrow one you have addressed is rarely valuable. You can’t address every possible case, so you must find ways to remain open to the range of possibilities, in such a way that the user can adapt your guidance to their needs.

In how-to guides, practical usability is more helpful than completeness. Whereas a tutorial needs to be a complete, end-to-end guide, a how-to guide does not. It should start and end in some reasonable, meaningful place, and require the reader to join it up to their own work.

A how-to guide describes an executable solution to a real-world problem or task. It’s in the form of a contract: if you’re facing this situation, then you can work your way through it by taking the steps outlined in this approach. The steps are in the form of actions.

“Actions” in this context includes physical acts, but also thinking and judgement - solving a problem involves thinking it through. A how-to guide should address how the user thinks as well as what the user does.

The fundamental structure of a how-to guide is a sequence. It implies logical ordering in time, that there is a sense and meaning to this particular order.

In many cases, the ordering is simply imposed by the way things must be (step two requires completion of step one, for example). In this case it’s obvious what order your directions should take.

Sometimes the need is more subtle - it might be possible to perform two operations in either order, but if for example one operation helps set up the user’s working environment or even their thinking in a way that benefits the other, that’s a good reason for putting it first.

At all times, try to ground your sequences in the patterns of the user’s activities and thinking, in such a way that the guide acquires flow: smooth progress.

Achieving flow means successfully understanding the user. Paying attention to sense and meaning in ordering requires paying attention to the way human beings think and act, and the needs of someone following directions.

Again, this can be somewhat obvious: a workflow that has the user repeatedly switching between contexts and tools is clearly clumsy and inefficient. But you should look more deeply than this. What are you asking the user to think about, and how will their thinking flow from subject to subject during their work? How long do you require the user to hold thoughts open before they can be resolved in action? If you require the user to jump back to earlier concerns, is this necessary or avoidable?

A how-to guide is concerned not just with logical ordering in time, but action taking place in time. Action, and a guide to it, has pace and rhythm. Badly-judged pace or disrupted rhythm are both damaging to flow.

At its best, how-to documentation gives the user flow. There is a distinct experience of encountering a guide that appears to anticipate the user - the documentation equivalent of a helper who has the tool you were about to reach for, ready to place it in your hand.

Choose titles that say exactly what a how-to guide shows.

- good: How to integrate application performance monitoring

- bad: Integrating application performance monitoring (maybe the document is about how to decide whether you should, not about how to do it)

- very bad: Application performance monitoring (maybe it’s about how - but maybe it’s about whether, or even just an explanation of what it is)

Note that search engines appreciate good titles just as much as humans do.

- This guide shows you how to…

- Describe clearly the problem or task that the guide shows the user how to solve.

- If you want x, do y. To achieve w, do z.

- Use conditional imperatives.

- Refer to the x reference guide for a full list of options.

- Don’t pollute your practical how-to guide with every possible thing the user might do related to x.

Consider a recipe, an excellent model for a how-to guide. A recipe clearly defines what will be achieved by following it, and addresses a specific question (How do I make…? or What can I make with…?).

It’s not the responsibility of a recipe to teach you how to make something. A professional chef who has made exactly the same thing multiple times before may still follow a recipe - even if they created the recipe themselves - to ensure that they do it correctly.

Even following a recipe requires at least basic competence. Someone who has never cooked before should not be expected to follow a recipe with success, so a recipe is not a substitute for a cooking lesson.

Someone who expected to be provided with a recipe, and is given instead a cooking lesson, will be disappointed and annoyed. Similarly, while it’s interesting to read about the context or history of a particular dish, the one time you don’t want to be faced with that is while you are in the middle of trying to make it. A good recipe follows a well-established format, that excludes both teaching and discussion, and focuses only on how to make the dish concerned.

Reference guides are technical descriptions of the machinery and how to operate it. Reference material is information-oriented.

Reference material contains propositional or theoretical knowledge that a user looks to in their work.

The only purpose of a reference guide is to describe, as succinctly as possible, and in an orderly way. Whereas the content of tutorials and how-to guides are led by needs of the user, reference material is led by the product it describes.

In the case of software, reference guides describe the software itself - APIs, classes, functions and so on - and how to use them.

Your users need reference material because they need truth and certainty - firm platforms on which to stand while they work. Good technical reference is essential to provide users with the confidence to do their work.

Reference material describes the machinery. It should be austere. One hardly reads reference material; one consults it.

There should be no doubt or ambiguity in reference; it should be wholly authoritative.

Reference material is like a map. A map tells you what you need to know about the territory, without having to go out and check the territory for yourself; a reference guide serves the same purpose for the product and its internal machinery.

Although reference should not attempt to show how to perform tasks, it can and often needs to include a description of how something works or the correct way to use it.

Unfortunately, too many software developers think that auto-generated reference material is all the documentation required.

Some reference material (such as API documentation) can be generated automatically by the software it describes, which is a powerful way of ensuring that it remains faithfully accurate to the code.

Neutral description is the key imperative of technical reference.

Style and form

- austere and uncompromising

- neutrality, objectivity, factuality

- structured according to the structure of the machinery itself

Unfortunately one of the hardest things to do is to describe something neutrally. It’s not a natural way of communicating. What’s natural on the other hand is to explain, instruct, discuss, opine, and all these things run counter to the needs of technical reference, which instead demands accuracy, precision, completeness and clarity.

It can be tempting to introduce instruction and explanation, simply because description can seem too inadequate to be useful, and because we do indeed need these other things. Instead, link to how-to guides, explanation and introductory tutorials.

Reference material is useful when it is consistent. Standard patterns are what allow us to use reference material effectively. Your job is to place the material that your user needs know where they expect to find it, in a format that they are familiar with.

There are many opportunities in writing to delight your readers with your extensive vocabulary and command of multiple styles, but reference material is definitely not one of them.

The way a map corresponds to the territory it represents helps us use the former to find our way through the latter. It should be the same with documentation: the structure of the documentation should mirror the structure of the product, so that the user can work their way through them at the same time.

It doesn’t mean forcing the documentation into an unnatural structure. What’s important is that the logical, conceptual arrangement of and relations within the code should help make sense of the documentation.

Examples are valuable ways of providing illustration that helps readers understand reference, while avoiding the risk of becoming distracted from the job of describing. For example, an example of usage of a command can be a succinct way of illustrating it and its context, without falling into the trap of trying to explain or instruct.

- Django’s default logging configuration inherits Python’s defaults. It’s available as

django.utils.log.DEFAULT_LOGGINGand defined indjango/utils/log.py - State facts about the machinery and its behaviour.

- Sub-commands are: a, b, c, d, e, f.

- List commands, options, operations, features, flags, limitations, error messages, etc.

- You must use a. You must not apply b unless c. Never d.

- Provide warnings where appropriate.

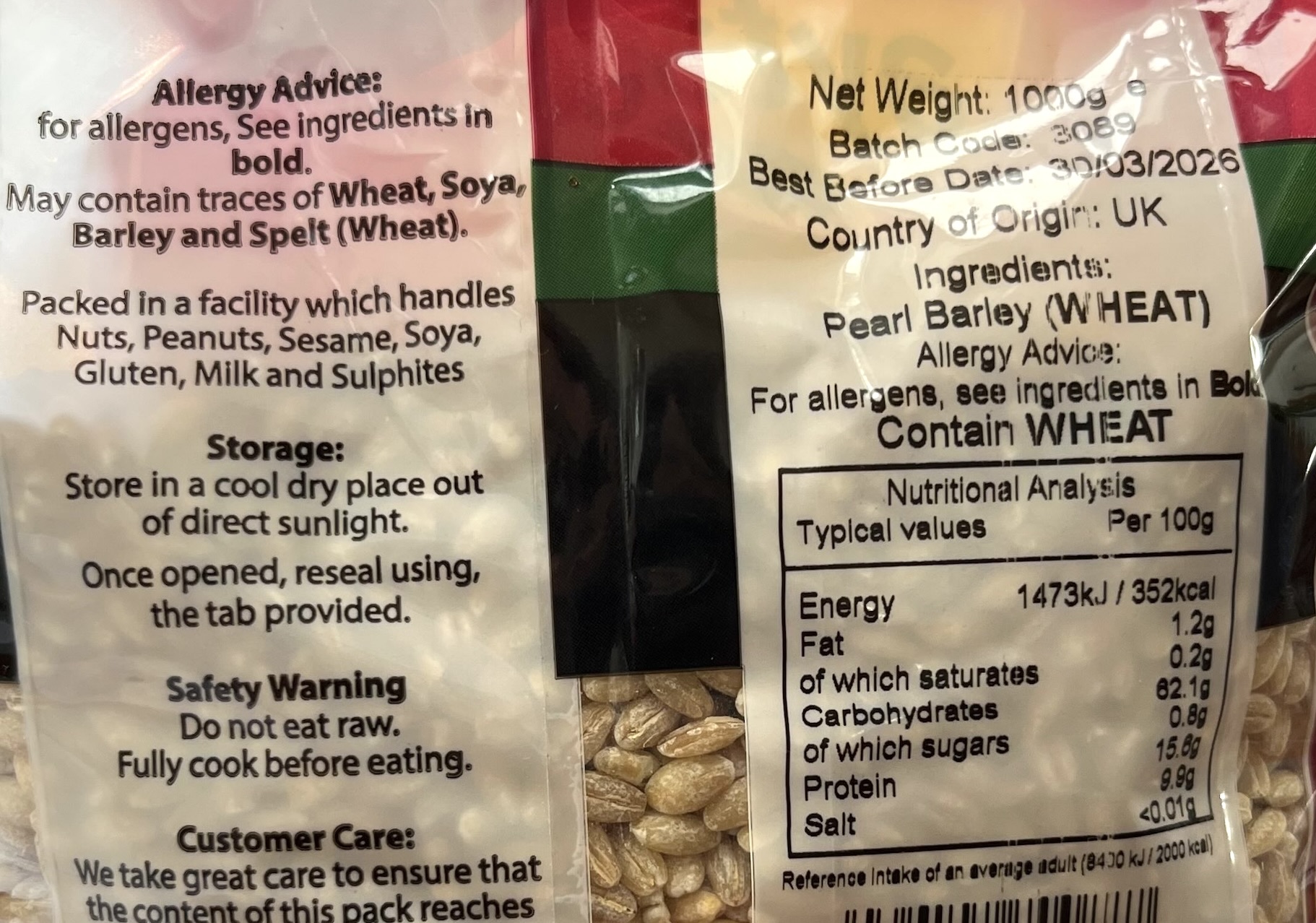

You might check the information on a packet of food, in order to help you make a decision about what to do.

When you’re looking for information - relevant facts - you do not want to be confronted by opinions, speculation, instructions or interpretation.

You also expect that information to be presented in standard ways, so that you - when you need to know about something’s nutritional properties, how it should be stored, its ingredients, what health implications it might have - can find them quickly, and know you can rely on them.

So you expect to see for example: May contain traces of wheat. Or: Net weight: 1000g.

You will certainly not expect to find for example recipes or marketing claims mixed up with this information; that could be literally dangerous.

The way reference material is presented on food products is so important that it’s usually governed by law, and the same kind of seriousness should apply to all reference documentation.

Explanation is a discusive treatment of a subject, that permits reflection. Explanation is understanding-oriented.

Explanation deepens and broadens the reader’s understanding of a subject. It brings clarity, light and context.

The concept of reflection is important. Reflection occurs after something else, and depends on something else, yet at the same time brings something new - shines a new light - on the subject matter.

The perspective of explanation is higher and wider than that of the other not types. It does not take the user’s eye-level view, as in a how-to guide, or a close-up view of the machinery, like reference material. Its scope in each case is a topic - “an area of knowledge”, that somehow has to be bounded in a reasonable, meaningful way.

For the user, explanation joins things together. It’s an answer to the question: Can you tell me about…?

It’s documentation that it makes sense to read while away from the product itself (one could say, explanation is the only kind of documentation that it might make sense to read in the bath).

Explanation is characterised by its distance from the active concerns of the practitioner. It doesn’t have direct implications for what they do, or for their work. This means that it’s sometimes seen as being of lesser importance. That’s a mistake; it may be less urgent than the other three, but it’s no less important. It’s not a luxury. No practitioner of a craft can afford to be without an understanding of that craft, and needs the explanatory material that will help weave it together.

Explanation by any other name

Your explanation documentation doesn’t need to be called Explanation. Alternatives include:

- Discussion

- Background

- Conceptual guides

- Topics

The word explanation - and its cognates in other languages - refer to unfolding, the revelation of what is hidden in the folds. So explanation brings to the light things that were implicit or obscured.

Similarly, words that mean understanding share roots in words meaning to hold or grasp (as in comprehend). That’s an important part of understanding, to be able to hold something or be in possession of it. Understanding seals together the other components of our mastery of a craft, and makes it safely our own.

Understanding doesn’t come from explanation, but explanation is required to form that web that helps hold everything together. Without it, the practitioner’s knowledge of their craft is loose and fragmented and fragile, and their exercise of it is anxious.

Quite often explanation is not explicitly recognised in documentation; and the idea that things need to be explained is often only faintly expressed. Instead, explanation tends to be scattered in small parcels in other sections.

It’s not always easy to write good explanatory material. Where does one start? It’s also not clear where to conclude. There is an open-endedness about it that can give the writer too many possibilities.

Tutorials, how-to-guides and reference are all clearly defined in their scope by something that is also well-defined: by what you need the user to learn, what task the user needs to achieve, or just by the scope of the machine itself.

In the case of explanation, it’s useful to have a real or imagined why question to serve as a prompt. Otherwise, you simply have to draw some lines that mark out a reasonable area and be satisfied with that.

When writing explanation you are helping to weave a web of understanding for your readers. Make connections to other things, even to things outside the immediate topic, if that helps.

Provide background and context in your explanation: explain why things are so - design decisions, historical reasons, technical constraints - draw implications, mention specific examples.

Things to discuss

- the bigger picture

- history

- choices, alternatives, possibilities

- why: reasons and justifications

Explanation guides are about a topic in the sense that they are around it. Even the names of your explanation guides should reflect this; you should be able to place an implicit (or even explicit) about in front of each title. For example: About user authentication, or About database connection policies.

Opinion might seem like a funny thing to introduce into documentation. The fact is that all human activity and knowledge is invested within opinion, with beliefs and thoughts. The reality of any human creation is rich with opinion, and that needs to be part of any understanding of it.

Similarly, any understanding comes from a perspective, a particular stand-point - which means that other perspectives and stand-points exist. Explanation can and must consider alternatives, counter-examples or multiple different approaches to the same question.

In explanation, you’re not giving instruction or describing facts - you’re opening up the topic for consideration. It helps to think of explanation as discussion: discussions can even consider and weigh up contrary opinions.

One risk of explanation is that it tends to absorb other things. The writer, intent on covering the topic, feels the urge to include instruction or technical description related to it. But documentation already has other places for these, and allowing them to creep in interferes with the explanation itself, and removes them from view in the correct place.

- The reason for x is because historically, y …

- Explain.

- W is better than z, because …

- Offer judgements and even opinions where appropriate.

- An x in system y is analogous to a w in system z. However …

- Provide context that helps the reader.

- Some users prefer w (because z). This can be a good approach, but…

- Weigh up alternatives.

- An x interacts with a y as follows: …

- Unfold the machinery’s internal secrets, to help understand why something does what it does.

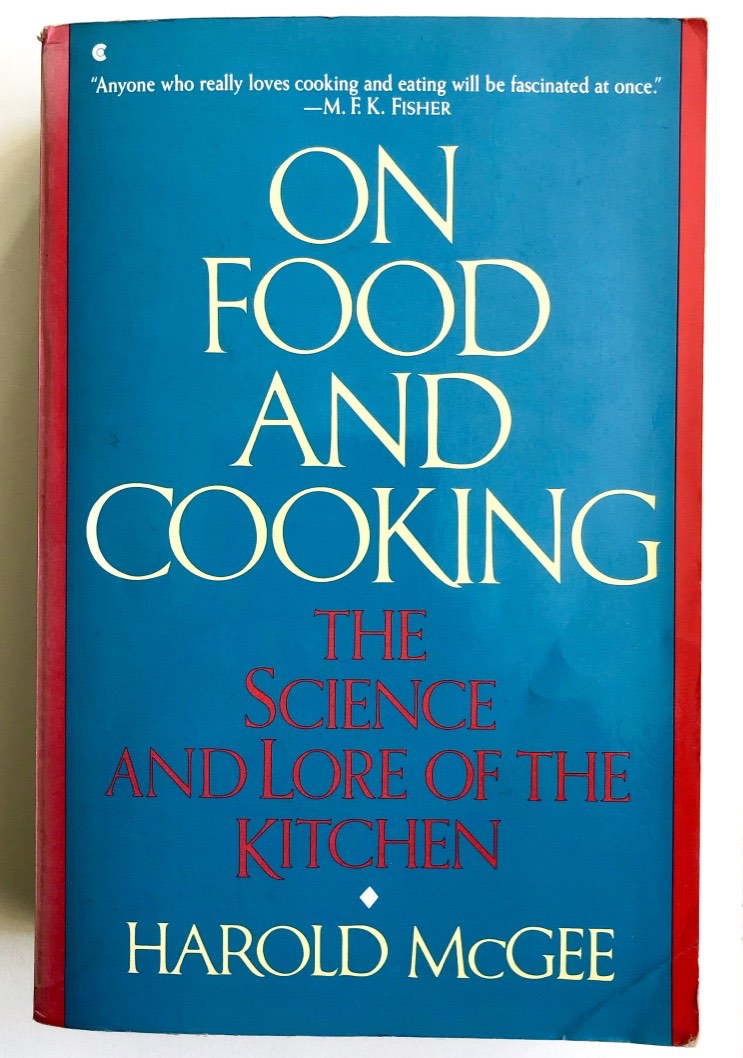

In 1984 Harold McGee published On food and cooking.

The book doesn’t teach how to cook anything. It doesn’t contain recipes (except as historical examples) and it isn’t a work of reference. Instead, it places food and cooking in the context of history, society, science and technology. It explains for example why we do what we do in the kitchen and how that has changed.

It’s clearly not a book we would read while cooking. We would read when we want to reflect on cooking. It illuminates the subject by taking multiple different perspectives on it, shining light from different angles.

After reading a book like On food and cooking, our understanding is changed. Our knowledge is richer and deeper. What we have learned may or may not be immediately applicable next time we are doing something in the kitchen, but it will change how we think about our craft, and will affect our practice.

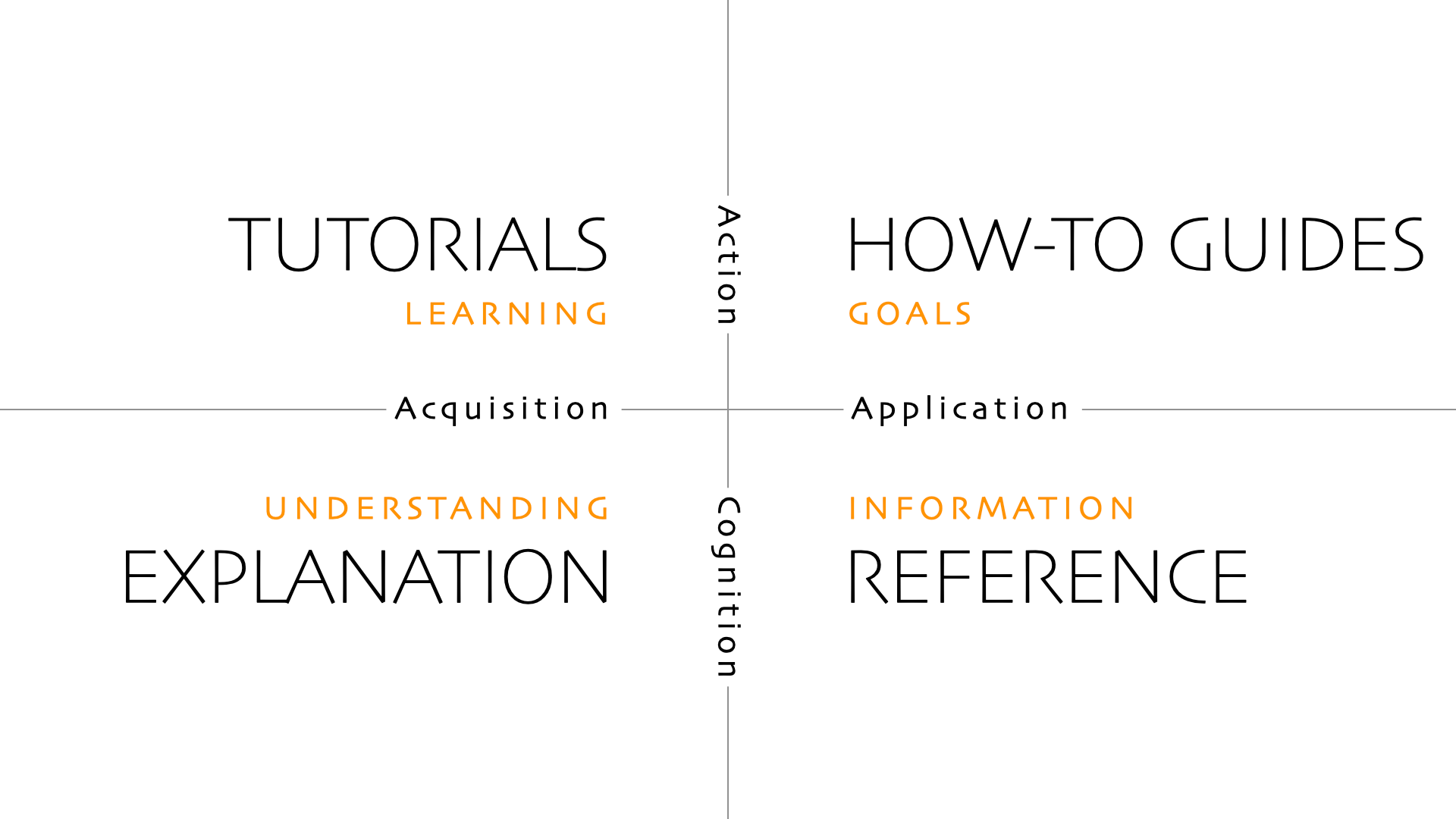

The Diátaxis map is an effective reminder of the different kinds of documentation and their relationship, and it accords well with intuitions about documentation.

However intuition is not always to be relied upon. Often when working with documentation, an author is faced with the question: what form of documentation is this? or what form of documentation is needed here? - and no obvious, intuitive answer.

Worse, sometimes intuition provides an immediate answer that is also wrong.

A map is most powerful in unfamiliar territory when we also have a compass to guide us.

The Diátaxis compass is something like a truth-table or decision-tree of documentation. It reduces a more complex, two-dimensional problem to its simpler parts, and provides the author with a course-correction tool.

| If the content… | …and serves the user’s… | … then it must belong to… |

|---|---|---|

| informs action | acquisition of skill | a tutorial |

| informs action | application of skill | a how-to guide |

| informs cognition | application of skill | reference |

| informs cognition | acquisition of skill | explanation |

The compass can be applied equally to user situations that need documentation, or to documentation itself that perhaps needs to be moved or improved. Like many good tools, it’s surprising banal.

To use the compass, just two questions need to be asked: action or cognition? acquisition or application?

And it yields the answer.

The compass is particularly effective when you think that you think you (or even the documentation in front of you) are doing one thing - but you are troubled by a sense of doubt, or by some difficulty in the work. The compass forces you to stop and reconsider.

Especially when you are trying to find your initial bearings, use the compass’s terms flexibly; don’t get fixated on the exact names.

- action: practical steps, doing

- cognition: theoretical or propositional knowledge, thinking

- acquisition: study

- application: work

And the questions themselves can also be used in different ways:

- Do I think I am writing for x or y?

- Is this writing in front of me engaged in x or y?

- Does the user need x or y?

- Do I want to x or y?

And try applying them close-up, at the level of sentences and words, or from a wider perspective, considering an entire document.

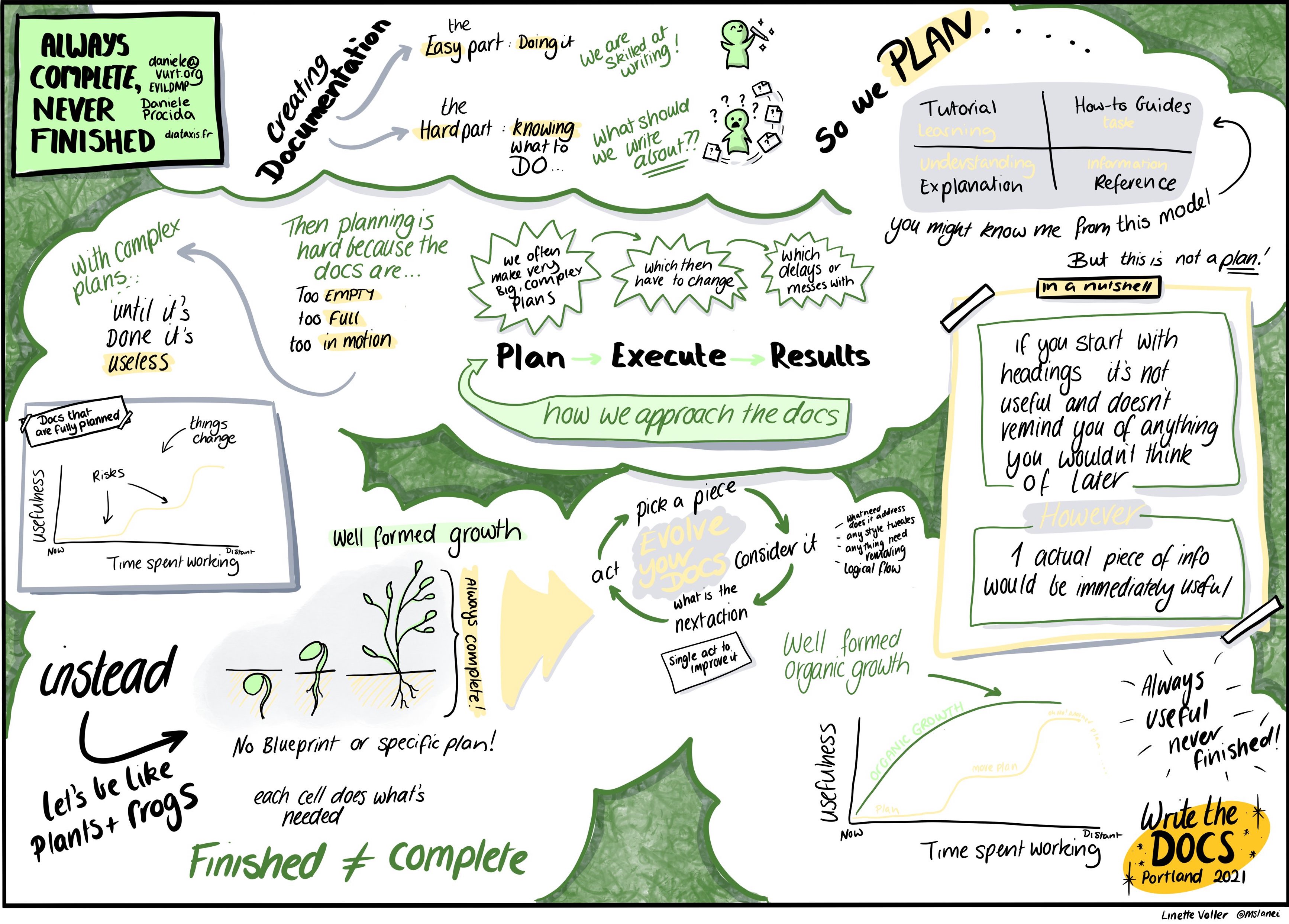

As well as providing a guide to documentation content, Diátaxis is also a guide to documentation process and execution.

Most people who work on technical documentation must make decisions about how to work, as they work. In some contexts, documentation must be delivered once, complete and in its final state, but it’s more usual that it’s an on-going project, for example developed alongside a product that itself evolves and develops. It’s also the experience of many people who work on documentation to find themselves responsible for improving or even remediating a body of work.

Diátaxis provides an approach to work that runs counter to much of the accepted wisdom in documentation. In particular, it discourages planning and top-down workflows, preferring instead small, responsive iterations from which overall patterns emerge.

Diátaxis describes a complete picture of documentation. However the structure it proposes is not intended to be a plan, something you must complete in your documentation. It’s a guide, a map to help you check that you’re in the right place and going in the right directions.

The point of Diátaxis is to give you a way to think about and understand your documentation, so that you can make better sense of what it’s doing and what you’re trying to do with it. It provides tools that help assess it, identify where its problems lie, and judge what you can do to improve it.

Although structure is key to documentation, using Diátaxis means not spending energy trying to get its structure correct.

If you continue to follow the prompts that Diátaxis provides, eventually your documentation will assume the Diátaxis structure - but it will have assumed that shape because it has been improved. It’s not the other way round, that the structure must be imposed upon documentation to improve it.

In practice, this means that getting started with Diátaxis doesn’t require thinking about dividing up your documentation into the four sections, or writing out headings to put material under.

Instead, following the workflow described in the next two sections, make changes where you see opportunities for improvement according to Diátaxis principles, so that the documentation starts to take a certain shape. At a certain point, the changes you have made will appear to demand that you move material under a certain Diátaxis heading - and that is how your top-level structure will form. In other words, Diátaxis changes the structure of your documentation from the inside.

Diátaxis strongly prescribes a structure, but whatever the state of your existing documentation - even if it’s a complete mess by any standards - it’s always possible to improve it, iteratively.

It’s natural to want to complete large tranches of work before you publish them, so that you have something substantial to show each time. Avoid this temptation - every step in the right direction is worth publishing immediately.

Although Diátaxis is intended to provide a big picture of documentation, don’t try to work on the big picture. It’s both unnecessary and unhelpful. Diátaxis is designed to guide small steps; keep taking small steps to arrive where you want to go.

If you’re tidying up a huge mess, the temptation is to tear it all down and start again. Again, avoid it. As far as improving documentation in-line with Diátaxis goes, it isn’t necessary to seek out things to improve. Instead, the best way to apply Diátaxis is as follows:

Choose something - any piece of the documentation. If you don’t already have something that you know you want to put right, don’t go looking for outstanding problems. Just look at what you have right in front of you at that moment: the file you’re in, the last page you read - it doesn’t matter. If there isn’t one just choose something, literally at random.

Assess it. Next consider this thing critically. Preferably it’s a small thing, nothing bigger than a page - or better, even smaller, a paragraph or a sentence. Challenge it, according to the standards Diátaxis prescribes: What user need is represented by this? How well does it serve that need? What can be added, moved, removed or changed to serve that need better? Do its language and logic meet the requirements of this mode of documentation?

Decide what to do. Decide, based on your answers to those questions: What single next action will produce an immediate improvement here?

Do it. Complete that next single action, and consider it completed - i.e. publish it, or at least commit the change. Don’t feel that you need to do anything else to make a worthy improvement.

And then go back to the beginning of the cycle.

Working like this helps reduce the stress of one of the most paralysing and troublesome aspects of the documentation-writer’s work: working out what to do. It keeps work flowing in the right direction, always towards the desired end, without having to expend energies on a plan.

There’s a strong urge to work in a cycle of planning and execution in order to work towards results. But it’s not the only way, and there are often better ways when working with documentation.

A good model for documentation is well-formed organic growth that adapts to external conditions. Organic growth takes place at the cellular level. The structure of the organism as a whole is guaranteed by the healthy development of cells, according to rules that are appropriate to each kind of cell. It’s not the other way round, that a structure is imposed on the organism from above or outside. Good structure develops from within.

It’s the same with documentation: by following the principles that Diátaxis provides, your documentation will attain a healthy structure, because its internal components themselves are well-formed - like a living organism, it will have built itself up from the inside-out, one cell at a time.

Consider a plant. As a living, growing organism, a plant is never finished - it can always develop further, move on to the next stage of growth and maturity. But, at every stage of its development, from seed to a fully-mature tree, it’s always complete - there’s never something missing from it. At any point, it is in a state that is appropriate to its stage of development.

Similarly, documentation is also never finished, because it always has to keep adapting and changing to the product and to users’ needs, and can always be developed and improved further.

However it can always be complete: useful to users, appropriate to its current stage of development, and in a healthy structural state and ready to go on to the next stage.

The Grand Unified Theory of Documentation

— David Laing

The pages in this section are intended to provide some theoretical grounding for the practices Diátaxis prescribes, and to explore some of the questions it raises.

Within the discipline of documentation, discourse tends towards the practical and concrete. The approach is generally heuristic: guidelines, rules of thumb, specific imperatives, principles that we know work.

As practitioners, we have much to say about what to do, and how to do it and how it works, and relatively little to say about why it works. Our sense of the right way to do things is largely based on a combination of intuition and experience. The theoretical aspect of the discipline receives far less attention.

Diátaxis aims to place documentation practice on a more rigorous theoretical footing.

In this section

These pages dig deeper into the thinking that underpins Diátaxis.

- Foundations - why Diátaxis works

- The map - documentation in two dimensions

- Towards a theory of quality in documentation

Common problems explored:

- The difference between a tutorial and how-to guide

- The difference between reference and explanation

- Diátaxis in complex hierarchies

Diátaxis is successful because it works - both users and creators have a better experience of documentation as a result. It makes sense and it feels right.

However, that’s not enough to be confident in Diátaxis as a theory of documentation. As a theory, it needs to show why it works. It needs to show that there is actually some reason why there are exactly four kinds of documentation, not three or five. It needs to demonstrate rigorous thinking and analysis, and that it stands on a sound theoretical foundation.

Otherwise, it will be just another useful heuristic approach, and the strongest claim we can make for it is that “it seems to work quite well”.

Diátaxis is based on the principle that documentation must serve the needs of its users. Knowing how to do that means understanding what the needs of users are.

The user whose needs Diátaxis serves is the practitioner in a domain of skill. A domain of skill is defined by a craft - the use of a tool or product is a craft. So is an entire discipline or profession. Using a programming language is a craft, as is flying a particular aircraft, or even being a pilot in general.

Understanding the needs of these users means in turn understanding the essential characteristics of craft or skill.

A skill or craft or practice contains both action (practical knowledge, knowing how, what we do) and cognition (theoretical knowledge, knowing that, what we think). The two are completely bound up with each other, but they are counterparts, wholly distinct from each from each, two different aspects of the same thing.

Similarly, the relationship of a practitioner with their practice is that it is something that needs to be both acquired, and applied. Being “at work” (concerned with applying the skill and knowledge of their craft) and being “at study” (concerned with acquiring them) are once again counterparts, distinct but bound up with each other.

This gives us two dimensions of skill, that we can lay out on a map - a map of the territory of craft:

This is a complete map. There are only two dimensions, and they don’t just cover the entire territory, they define it. This is why there are necessarily four quarters to it, and there could not be three, or five. It is not an arbitrary number.

It also shows us the qualities of craft that define each of them. When the idea that documentation must serve the needs of craft is applied to this map, it reveals in turn what documentation must be and do to fulfil those obligations - in four distinct ways.

The map of the territory of craft is what gives us the familiar Diátaxis map of documentation. The map is in effect an answer to the question: what must documentation do to align with these qualities of skill, and to what need is it oriented in each case?

We can see how the map of documentation addresses needs across those two dimensions, each need also defined by the characteristics of its quarter of the map.

| need | addressed in | the user | the documentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| learning | tutorials | acquires their craft | informs action |

| goals | how-to guides | applies their craft | informs action |

| information | reference | applies their craft | informs cognition |

| understanding | explanation | acquires their craft | informs cognition |

The Diátaxis map of documentation is a memorable and approachable idea. But, a map is only reliable if it adequately describes a reality. Diátaxis is underpinned by a systematic description and analysis of generalised user needs.

This is why the tutorials, how-to guides, reference and explanation of Diátaxis are a complete enumeration of the types of documentation that serve practitioners in a craft. This is why there are four and only four types of documentation. There is simply no other territory to cover.

One reason Diátaxis is effective as a guide to organising documentation is that it describes a two-dimensional structure, rather than a list.

It specifies its types of documentation in such a way that the structure naturally helps guide and shape the material it contains.

As a map, it places the different forms of documentation into relationships with each other. Each one occupies a space in the mental territory it outlines, and the boundaries between them highlight their distinctions.

When documentation fails to attain a good structure, it’s rarely just a problem of structure (though it’s bad enough that it makes it harder to use and maintain). Architectural faults infect and undermine content too.

In the absence of a clear, generalised documentation architecture, documentation creators will often try to structure their work around features of a product.

This is rarely successful, even in a single instance. In a portfolio of documentation instances, the results are wild inconsistency. Much better is the adoption of a scheme that tries to provide an answer to the question: how to arrange documentation in general?

In fact any orderly attempt to organise documentation into clear content categories will help improve it (for authors as well as users), by providing lists of content types.

Even so, authors often find themselves needing to write particular documentation content that fails to fit well within the categories put forward by a scheme, or struggling to rewrite existing material. Often, there is a sense of arbitrariness about the structure that they find themselves working with - why this particular list of content types rather than another? And if another competing list is proposed, which to adopt?

A clear advantage of organising material this way is that it provides both clear expectations (to the reader) and guidance (to the author). It’s clear what the purpose of any particular piece of content is, it specifies how it should be written and it shows where it should be placed.

| Tutorials | How-to guides | Reference | Explanation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| what they do | introduce, educate, lead | guide | state, describe, inform | explain, clarify, discuss |

| answers the question | “Can you teach me to…?” | “How do I…?” | “What is…?” | “Why…?” |

| oriented to | learning | goals | information | understanding |

| purpose | to provide a learning experience | to help achieve a particular goal | to describe the machinery | to illuminate a topic |

| form | a lesson | a series of steps | dry description | discursive explanation |

| analogy | teaching a child how to cook | a recipe in a cookery book | information on the back of a food packet | an article on culinary social history |

Each piece of content is of a kind that not only has one particular job to do, that job is also clearly distinguished from and contrasted with the other functions of documentation.

Most documentation systems and authors recognise at least some of these distinctions and try to observe them in practice.

However, there is a kind of natural affinity between each of the different forms of documentation and its neighbours on the map, and a natural tendency to blur the distinctions (that can be seen repeatedly in examples of documentation).

| guide action | tutorials | how-to guides |

| serve the application of skill | reference | how-to guides |

| contain propositional knowledge | reference | explanation |

| serve the acquisition of skill | tutorials | explanation |

When these distinctions are allowed to blur, the different kinds of documentation bleed into each other. Writing style and content make their way into inappropriate places. It also causes structural problems, which make it even more difficult to maintain the discipline of appropriate writing.

In the worst case there is a complete or partial collapse of tutorials and how-to guides into each other, making it impossible to meet the needs served by either.

Diátaxis is intended to help documentation better serve users in their cycle of interaction with a product.

This phrase should not be understood too literally. It is not the case that a user must encounter the different kinds of documentation in the order tutorials > how-to guides > technical reference > explanation. In practice, an actual user may enter the documentation anywhere in search of guidance on some particular subject, and what they want to read will change from moment to moment as they use your documentation.

However, the idea of a cycle of documentation needs, that proceeds through different phases, is sound and corresponds to the way that people actually do become expert in a craft. There is a sense and meaning to this ordering.

- learning-oriented phase: We begin by learning, and learning a skill means diving straight in to do it - under the guidance of a teacher, if we’re lucky.

- goal-oriented phase: Next we want to put the skill to work.

- information-oriented phase: As soon as our work calls upon knowledge that we don’t already have in our head, it requires us to consult technical reference.

- explanation-oriented phase: Finally, away from the work, we reflect on our practice and knowledge to understand the whole.

And then it’s back to the beginning, perhaps for a new thing to grasp, or to penetrate deeper.

Diátaxis is an approach to quality in documentation.

“Quality” is a word in danger of losing some of its meaning; it’s something we all approve of, but rarely risk trying to describe in any rigorous way. We want quality in our documentation, but much less often specify what exactly what we mean by that.

All the same, we can generally point to examples of “high quality documentation” when asked, and can identify lapses in quality when we see them - and more than that, we often agree when we do. This suggests that we still have a useful grasp on the notion of quality.

As we pursue quality in documentation, it helps to make that grasp surer, by paying some attention to it - here, attempting to refine our grasp by positing a distinction between functional quality and deep quality.

We need documentation to meet standards of accuracy, completeness, consistency, usefulness, precision and so on. We can call these aspects of its functional quality. Documentation that fails to meet any one of them is failing to perform one of its key functions.

These properties of functional quality are all independent of each other. Documentation can be accurate without being complete. It can be complete, but inaccurate and inconsistent. It can be accurate, complete, consistent and also useless.

Attaining functional quality means meeting high, objectively-measurable standards in multiple independent dimensions, consistently. It requires discipline and attention to detail, and high levels of technical skill.

To make it harder for the creator of documentation, any failure to meet all of these standards is readily apparent to the user.

There are other characteristics, that we can call deep quality.

Functional quality is not enough, or even satisfactory on its own as an ambition. True excellence in documentation implies characteristics of quality that are not included in accuracy, completeness and so on.

Think of characteristics such as:

- feeling good to use

- having flow

- fitting to human needs

- being beautiful

- anticipating the user

Unlike the characteristics of functional quality, they cannot be checked or measured, but they can still be clearly identified. When we encounter them, we usually (not always, because we need to be capable of it) recognise them.

They are characteristics of deep quality.

Aspects of deep quality seem to be genuinely distinct in kind from the characteristics of functional quality.

Documentation can meet all the demands of functional quality, and still fail to exhibit deep quality. There are many examples of documentation that is accurate and consistent (and even very useful) but which is also awkward and unpleasant to use.

It’s also noticeable that while characteristics of functional quality such as completeness and accuracy are independent of each other, those of deep quality are hard to disentangle. Having flow and anticipating the user are aspects of each other - they are interdependent. It’s hard to see how something could feel good to use without fitting to our needs.

Aspects of functional quality can be measured - literally, with numbers, in some cases (consider completeness). That’s clearly not possible with qualities such as having flow. Instead, such qualities can only be enquired into, interrogated. Instead of taking measurements, we must make judgements.

Functional quality is objective - it belongs to the world. Accuracy of documentation means the extent to which it conforms to the world it’s trying to describe. Deep quality can’t be ascertained by holding something up to the world. It’s subjective, which means that we can assess it only in the light of the needs of the subject of experience, the human.

And, deep quality is conditional upon functional quality. Documentation can be accurate and complete and consistent without being truly excellent - but it will never have deep quality without being accurate and complete and consistent. No user of documentation will experience it as beautiful, if it’s inaccurate, or enjoy the way it anticipates their needs if it’s inconsistent. The moment we run into such lapses the experience of documentation is tarnished.

Finally, all of the characteristics of functional quality appear to us, as documentation creators, as burdens and constraints. Each one of them represents a test or challenge we might fail. Or, even if we have met one now, we can never rest, because the next release or update means that we’ll have to check our work once again, against the thing that it’s documenting. Characteristics such as anticipating needs or flow, on the other hand, represent liberation, the work of creativity or taste. To attain functional quality in our work, we must conform to constraints; to attain deep quality we must invent.

| Functional quality | Deep quality |

|---|---|

| independent characteristics | interdependent characteristics |

| objective | subjective |

| measured against the world | assessed against the human |

| a condition of deep quality | conditional upon functional quality |

| aspects of constraint | aspects of liberation |

Consider how we judge the quality of say, clothing. Clothes must have functional quality (they must keep us appropriately warm and dry, stand up to wear). These things are objectively measurable. You don’t really need to know much about clothes to assess how well they do those this. If water gets in, or the clothing falls apart - it lacks quality.

There are other characteristics of quality in clothing that can’t simply be measured objectively, and to recognise those characteristics, we need to have an understanding of clothing. The quality of materials or workmanship isn’t always immediately obvious. Being able to judge that an item of clothing hangs well, moves well or has been expertly shaped requires developing at least a basic eye for those things. And these are its characteristics of deep quality.

But: even someone who can’t recognise, or fails to understand, those characteristics - who cannot say what they are - can still recognise very well that the clothing is excellent, because they find it that it feels good to wear, because it’s such that they want to wear it. No expertise is required to realise that clothing does or doesn’t feel comfortable as you move in it, that it fits and moves with you well. Your body knows it.

And it’s the same in documentation. Perhaps you need to be a connoisseur to recognise what it is that makes some documentation excellent, but that’s not necessary to be able to realise that it is excellent. Good documentation feels good; you feel pleasure and satisfaction when you use it - it feels like it fits and moves with you.

The users of our documentation may or may not have the understanding to say why it’s good, or where its quality lapses. They might recognise only the more obvious aspects of functional quality in it, mistaking those for its deeper excellence. That doesn’t matter - it will feel good, or not, and that’s what is important.

But we, as its creators, need a clear and effective understanding of what makes documentation good. We need to develop our sense of it so that we recognise what is good about it, as well as that it is good. And we need to develop an understanding of how people will feel when they’re using it.

Producing work of deep quality depends on our ability to do this.

Functional quality’s obligations are met through conscientious observance of the demands of the craft of documentation. They require solid skill and knowledge of the technical domain, the ability to gather up a complete terrain into a single, coherent, consistent map of it.

Diátaxis cannot address functional quality in documentation. It is concerned only with certain aspects of deep quality, some more than others - though if all the aspects of deep quality are tangled up in each other, then it affects all of them.

Although Diátaxis cannot address, or give us, functional quality, it can still serve it.

It works very effectively to expose lapses in functional quality. It’s often remarked that one effect of applying Diátaxis to existing documentation is that problems in it suddenly become apparent that were obscured before.

For example: the Diátaxis approach recommends that the architecture of reference documentation should reflect the architecture of the code it documents. This makes gaps in the documentation much more clearly visible.

Or, moving explanatory verbiage out of a tutorial (in accordance with Diátaxis demands) often has the effect of highlighting a section where the reader has been left to work something out for themselves.

But, as far as functional quality goes, Diátaxis principles can have only an analytical role.

In deep quality on the other hand, the Diátaxis approach can do more.

For example, it helps documentation fit user needs by describing documentation modes that are based on them; its categories exist as a response to needs.

We must pay attention to the correct organisation of these categories then, and the arrangement of its material and the relationships within them, the form and language adopted in different parts of documentation - as a way of fitting to user needs.

Or, in Diátaxis we are directly concerned with flow. In flow - whether the context is documentation or anything else - we experience a movement from one stage or state to another that seems right, unforced and in sympathy with both our concerns of the moment, and the way our minds and bodies work in general.

Diátaxis preserves flow by helping prevent the kind of disruption of rhythm that occurs when something runs across our purpose and steady progress towards it (for example when a digression into explanation interrupts a how-to guide).

And so on.

It’s important to understand that Diátaxis can never be all that is required in the pursuit of deep quality.

For example, while it can help attain beauty in documentation, at least in its overall form, it doesn’t by itself make documentation beautiful.

Diátaxis offers a set of principles - it doesn’t offer a formula. It certainly cannot offer a short-cut to success, bypassing the skills and insights of disciplines such as user experience or user interaction design, or even visual design.

Using Diátaxis does not guarantee deep quality. The characteristics of deep quality are forever being renegotiated, reinterpreted, rediscovered and reinvented. But what Diátaxis can do is lay down some conditions for the possibility of deep quality in documentation.

In Diátaxis, tutorials and how-to guides are strongly distinguished. It’s a distinction that’s often not made; in fact the single most common conflation made in software product documentation is that between the tutorial and the how-to guide.

So: what is the difference between tutorials and how to-guides? Why does it matter? And why do they get confused?

These are all good questions. Let’s start with the last one. If the distinction is really so important, why isn’t it more obvious?

In important respects, tutorials and how-to guides are indeed similar. They are both practical guides: they contain directions for the user to follow. They’re not there to explain or convey information. They exist to guide the user in what to do rather than what there is to know or understand.

They both set out steps for the reader to follow, and they both promise that if the reader follows those steps, they’ll arrive at a successful conclusion. Neither of them make much sense except for the user who has their hands on the machinery, ready to do things. They both describe ordered sequences of actions. You can’t expect success unless you perform the actions in the right order.

They are closely related, and like many close relations, can be mistaken for one another at first glance.

Diátaxis insists that what matters in documentation is the needs of the user, and it’s by paying attention to this that we can correctly distinguish between tutorials and how-to guides.

Sometimes the user is at study, and sometimes the user is at work. Documentation has to serve both those needs.

A tutorial serves the needs of the user who is at study. Its obligation is to provide a successful learning experience. A how-to guide serves the needs of the user who is at work. Its obligation is to help the user accomplish a task. These are completely different needs and obligations, and they are why the distinction between tutorials and how-to guides matters: tutorials are learning-oriented, and how-to guides are task-oriented.

We can consider this from the perspective of an actual example. Let’s say you’re in medicine: a doctor, someone who needs to acquire and apply the practical, clinical skills of their craft.

As a doctor, sometimes you will be in work situations, applying your skills, and sometimes you will be in study situations, acquiring skills (all good doctors, even those with long careers behind them, continue to study to improve their skills).

Early on in your training, you’ll learn how to suture a wound. You’ll start in the lab with your fellow students, at benches with small skin pads in front of you (skin pads are blocks of synthetic material in various layers that represent the epidermis, fat and other tissues. They have a similar hardness and texture to human flesh, and behave somewhat similarly when they’re cut and stitched). You’ll be provided with exactly what you need - gloves, scalpel, needle, thread and so on - and step-by-step you’ll be shown what to do, and what will happen when you do it.

And then it’s your turn. You will pick up the scalpel and tentatively draw it across the top of the pad, and make an ineffectual incision into the top layer (maybe a teaching assistant will tease you, asking what this poor pad has done, that it deserves such a nasty scratch). Your neighbour will look dismayed at their own attempt, a ragged cut of wildly uneven depths that looks like something from a knife-fight.

After a few attempts, with feedback and correction from the tutor, you’ll have made a more or less clean cut that mostly goes through the fat layer without cutting into the muscle beneath. Triumph!

But now you’re being asked to stitch it back up again! You’ll watch the tutor demonstrate deftly and precisely, closing the wound in the pad with a few neat, even stitches. You, on the other hand, will fumble with the thread. You will hold things in the wrong hand and the wrong way round and put them down in the wrong places. You will drop the needle. The thread will fall out. You will be told off for failing to maintain sterility.

Eventually, you’ll actually get to stitch the wound. You will puncture the skin in the wrong places and tear the edges of the cut. Your final result will be an ugly scene of stretched and puckered skin and crude, untidy stitches. The teaching assistants will have some critical things to say even about parts of it that you thought you’d got right.

But, you will have stitched your first wound. And you will come back to this lesson again and again, and bit by bit your fumbling will turn into confident practice. You will have acquired basic competence. You will have learned by doing.

This is a tutorial. It’s a lesson, safely in the hands of an instructor, a teacher who looks after the interests of a pupil.

Now, let’s think about the doctor at work. As a doctor at work, you are already competent. You have learned and refined clinical skills such as suturing, as well as many others, and you’re able to put them together on a daily basis to apply them to medical situations in the real world.

Consider a standard appendectomy. A clinical manual will list the equipment and personnel required in the theatre. It will show how to station the members of the team, and how to lay out the required tools, stands and monitors. It will proceed step-by-step through the actions the team will need to follow, ending with the formal handover to the post-operative team.

The manual will show what incisions need to be made where, but they will depend on whether you’re performing an open or a laparoscopic procedure, whether you have pre-operative imaging to rely on or not, and so on. It will include special steps or checks to be made in the case of an infant or juvenile patient, or when converting to an open appendectomy mid-procedure. Many of the steps will be of the form if this, then that.

Having a manual helps ensure that all the steps are done in the right order and none are omitted. As a team, you’ll check through details of a procedure to remind yourselves of key steps; sometimes you’ll refer to it during the procedure itself.

Even for routine surgical operations, clinical manuals contain lists of steps and checks. These manuals are how-to guides. They are not there to teach you - you already have your skills. You already know these processes. They are there to guide you safely in your clinical practice to accomplish a particular task - they serve your work.

The distinction between a lesson in medical school and a clinical manual is the distinction between a tutorial and a how-to guide.